Describing what it looks like when an organization “embraces scientific thinking” has evolved over the years at the Shingo Institute. If the reader was to look at the Shingo Model™ and Guidelines published just three years ago (2012), one would see a focus on training all associates in a “common understanding, approach, and language regarding improvement…(which) places a premium on defining and communicating desired outcomes…through a variety of models such as PDCA, the QI Story, A3 thinking and DMAIC.”

Today however, the definition of the principle focuses on the role of “cycles of experimentation, direct observation and learning” in driving improvements. And while the Shingo Institute still gives attention to the specific methodology used for practicing the scientific method, more emphasis is now placed on how organizations more generally “engage employees in teaching, modeling and thinking scientifically…[to] make decisions and experiment with good data…and seek the wisdom of others through collaboration.”

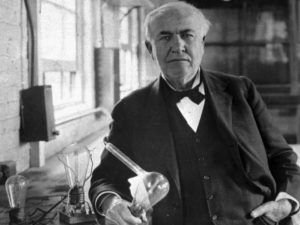

This focus on engagement, experimentation and collaboration harkens back to one of our most notable American inventors and businessmen, Thomas A. Edison. Dubbed “The Wizard of Menlo Park,” Edison held 1,093 US patents in his name, as well as numerous patents in the United Kingdom, France and Germany. He was also one of the first inventors to apply the principles of mass production and large-scale teamwork to the process of invention, and he is often credited with the creation of the first industrial research laboratory.

And while Edison was widely-known for systematically applying the scientific method to his work, historian Thomas Hughes (1977) detailed many points about Edison’s methods, which at first may seem at odds with many people’s view of the scientific method being a fixed series of steps applied in a logical and consistent sequence based on extensive facts and data.

While Edison made use of observation, measurement and experimentation in the formulation, testing and modification of his hypotheses, he was also known to extensively use a “hunt and try” (trial and error) approach to innovation. Further, Edison relied on his ability to be charismatic to leverage the ideas of others and was above all obsessive in pursuit of his desired outcomes.

“I owe my success to the fact that I never had a clock in my workroom. Seventy-five of us worked twenty hours everyday and slept only four hours – and thrived on it.” – Thomas Edison

In addition to facts and data, Edison used his ability to manipulate ideas on paper through effective sketching and to use metaphors to guide his thinking, gaining buy-in from his team and to envision the next steps. But perhaps what I find most interesting is the ease with which he blended team-based collaboration, the voice of the customer, and good old-fashioned public relations to establish new global industries with his inventions like the electric light, power utilities, sound recording and motion pictures.

To do this, he resisted a “rigid approach” to applying the scientific method and created environments where man, material, method and madness came together in an intense incubator and science collided with art through daily team-based innovation. As Tim Brown put it, “his approach was intended not to validate preconceived hypotheses but to help experimenters learn something new from each iterative stab.”

So what can Edison’s approach to innovation and industry teach us about what it means to embrace scientific thinking?

First, be wary of equating the principle of embracing scientific thinking with rolling out a “standard” approach to solving problems. The scientific method should be considered more as general principles and less a fixed sequence of steps to be followed the same way each and every time. When done well, not all the steps take place in every inquiry and are not always in the same order or to the same degree.

Second, leadership matters. If you want people to embrace thinking a new way, they have to feel a connection to the outcome. There has to be a worthwhile purpose to the problems they solve so they can inspire themselves and each other each time they engage in continuous improvement. Leaders provide a critical link between organizational vision and individual motivation. The better leaders help team members feel passion to the process of solving problems, the deeper the level of buy-in.

Finally, the voice of the customer is king. Edison was relentless in his desire to create innovations that were marketable to a mass audience. If the customer didn’t want it, he wasn’t interested in inventing it. All too often organizations are far too concerned with the system of solving problems and not near enough with the value of the problems being solved. Scientific thinking begins to focus more on the tools and techniques used and less on the value being created.

In the end, to “embrace scientific thinking” is an active and evolving process where leaders create an environment which inspires and encourages everyone to focus on what truly matters, seek to learn and grow through observation and experimentation, and solves problems each and everyday through a thorough understanding of the principles of the scientific method as opposed to procedures.

Leave a Reply